Professional Profile: Air-cooled Artisan Matt Hasara

How natural talent, an insistent mother, and a multi-dimensional passion gave rise to a peculiar career.

There is something special about taking a particular technology to its limit. New technology often replaces old technology prematurely, before the old technology can be fully appreciated, explored, and lived in, before the breadth of its delight has been discovered and before discovering whether any of its narrow corridors of possibility lead to unknown cathedrals. By increasing power, new technology relieves us from having to pay close attention to how we use our current knowhow, reduces the scope of our application, and narrows the faculties we are able to indulge in its operation.

Occasionally the beauty of old technology is sufficiently overwhelming that we are able to preserve it even against the onslaught of power and the cheaper price of its replacement. Sailboats remain not because they are fast and convenient, but because sailing naturally engages one’s whole being as a condition of operation. Modern careers are similar. Many of us, in return for higher pay, give up the sailboat-like career to earn more money working as cogs in the machine. What is fascinating about Matt’s career is that he has shown that the very endeavor of preserving and extending such technology can itself enable a career that is deeper and broader than is otherwise available.

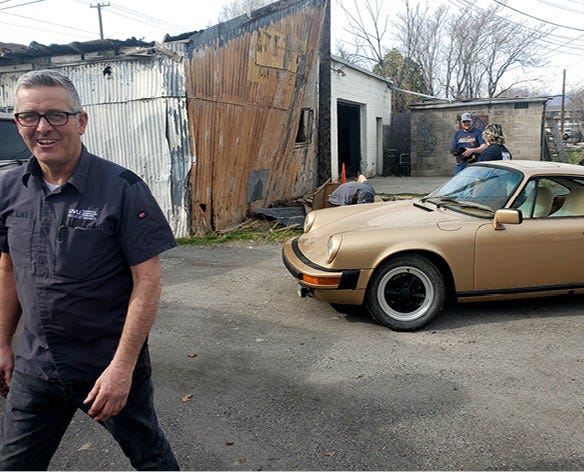

I met Matt two years ago, referred by a friend when I was trying to fix up an old 911sc, but Matt’s career can be traced all the way back to the tender age of 14 when he lived in the south end of San Jose, CA. That’s how old Matt was when his insistent mother all but drug him down to the garage of Carl Beckle, a six-foot-four-inch tall nuclear engineer complete with white shirt, thick glasses and a pocket protector employed by General Electric during the day but who worked on and raced Porsches by night. “He took me out to the garage and there are three 356 Porsches. 356 Porsches are 1965 and back. One that he was restoring, one that was his daily driver, a coupe, and then he had an original speedster which is now worth half a million or better with the factory installed single roll bar, hoops over the head and all that that he autocrossed. So this geek guy had three 356’s in his garage and he did all the work there and he did it all on his own…I was completely and totally enthralled.”

Air-cooled engines are combustion engines that do not rely on liquid coolant pumped through chambers in the engine to cool the engine but rather dissipate heat directly into the air. Air-cooled engines are simpler in many ways because they do not require coolant, pumps, and additional cavities for coolant to flow through. This simplicity becomes manifest particularly in sports cars by enabling smaller size and a lower profile. As liquid-cooled engines became more popular in the sixties sparking the muscle car era, persistence with air-cooled engines by some companies extended the older evolutionary path by allowing cars to remain smaller with lower centers of gravity enabling tighter translation of the driver’s intentions into the car’s movement. The lack of horsepower - a measure which liquid coolant enables an engine to reach much higher levels of - is partly compensated for by the agility and improved handling that comes from having a smaller car closer to the road. Continued dedication to an older technology by companies like Porsche opened compelling domains of design closed off to the more sophisticated newer tech. There is a tightness that is experienced in an air-cooled Porsche 911 that is missing in a Mustang or Camaro, or even in a new, larger liquid-cooled 911 even though the air-cooled car can no longer compete with any of these in a race.

From then on Matt spent his own evenings handing Carl tools and absorbing all the knowledge he could until around age 16 when Carl began helping Matt on his first car. At Carl’s recommendation Matt had purchased a Type 1 Volkswagen Beetle - another air-cooled car that came with a more affordable price tag than a Porsche 356. Together they dropped and tuned the engine, lowered the front end, put in new single-piece windows, painted it black and put in a solid dash with Porsche gauges. He sold that car at age 19 before embarking on a two-year mission for his church to Italy where he confesses he convinced more owners of Alpha Romeos and Lancias to let him drive their car than a missionary probably should have.

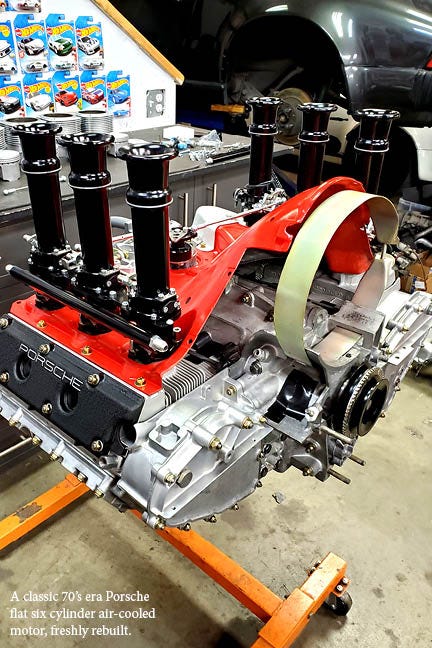

Finally at age 21 he was able to buy his first Porsche, a 914 which became the key to helping him squeeze his first dollar of income out of his zeal for cars. He realized he could make a good profit by buying 914’s in Utah, fixing them up, and then selling them in California. He was still operating primarily on the knowledge he gained working in Carl’s garage and then in the early 80’s he met Kevin Kuhle who owned Kevin’s German Auto Service. Kevin hired Matt. Kevin was a relentless personality with an obsession for detail, a trait important for building engines. It was Kevin who taught Matt how to build Porsche engines from the ground up and I’ve never been in Matt’s shop at a time that he didn’t have multiple flat sixes in the process of restoration. Once, after a malfunction on the race track in Mesquite, Nevada Kevin and Matt drove the limping 1978 911sc five hours back to Utah and without going home dropped and tore down the engine finding a broken piston in the wee hours of the morning. The intense few years Matt worked and raced with Kevin would prove to be the formative educational experience that powered his career.

An undervalued aspect of one’s career may be the adjacent hobbies and non-monetary enhancements to life it enables. Unsurprisingly racing pairs well with air-cooled expertise. Matt has never made serious money racing, it’s always been done for the fun. Besides cars, Matt has raced snowmobiles, vintage snowmobiles and jet skies. He pointed out an interesting nuance to me about safety. He claims he feels much safer on the track driving 150 mph inches behind another car and nearly touching doors with another, than he does going 75 on the interstate. He contends that on the interstate you never know who’s on valium, about to fall asleep, or otherwise suicidal. Teenagers, another potential catastrophe of interstates, also don’t generally exist on race tracks. The speeds may be higher, but the drivers are skilled and actually more focused on not dying than your average freeway traveler. Despite Matt’s conclusion that tracks are safer than freeways, he concedes the adrenaline runs higher on the track which is much of the point of going there. It’s a reminder to me about how our biological risk-notification systems have become unsynced from real risk as the environment has changed more quickly than our bodies. The risk difference between the track and the interstate is probably smaller than our adrenaline informs us of for the reasons Matt argued. What other misguided paths may such poorly tuned intuitions guide us down professionally? The risks of cubicles and air-conditioning mostly fail to register. We don’t see cardiovascular disease coming. Perhaps a curse of modernity is taking risks for which we get no adrenaline hit. Like a robot.

What is most interesting about Matt’s love of racing to me is its adjacency to his profession. His daily work is not 100% passion. Building engines or welding on new fenders may be fun but spending 20 hours removing and replacing the air-conditioning tubing on a 40 year-old Porsche, or spending 50 hours rewiring someone’s DIY-gone-wrong attempt to wire their own restoration, although more enjoyable for Matt than writing emails, is not what he always dreamed of doing. But how many of us have a passionate application for our professional skills? If it’s too much to ask to make our living doing something interesting, can we at least have a profession which bestows a skillset with non-professional, directly delightful applications? Together racing, body work, mechanical work, teaching and motor sales formed an interdependent ecosystem that powered Matt’s leisure and economic life. Matt’s skills have both professional and leisure payoffs that are different and in that way are immensely practical and such an arrangement is perhaps more achievable than earning income directly from one’s passions. Matt didn’t make his money racing, but rather by applying skills inherent to racing in other ways. Such adjacency enables the natural desire we have in pursuit of those activities to motivate a natural curiosity about and cultivation of those skills which also have professional payoff. I fear these days we have too much separation between our professional and leisurely endeavors and, measure professional success primarily in dollars, we fail to count the cost of having professional skills that are completely worthless in our non-professional, personal lives.

After working for Kevin, Matt opened his first business, German Motor Sports where he did both body work and mechanics. And then around 1988 a friend named Dustin Sweeten convinced Matt to become partners with him and to combine their respective businesses. Together they opened Alpine Power Sports where they sold, rented, and repaired snowmobiles, ATV’s (both of which were often air-cooled), jet skis and waverunners. For ten years they were nearly the only major power sports company in Utah and together they built the biggest Arctic Cat dealer in the western United States. Through all of this the air-cooled Porsche business remained constant, operating out of the same facility.

In 2010 a local university approached Matt to teach a small-engine night class. It was something Matt said he could never have done at 30 years old before he was an expert, but that he found enthralling after having accrued so much practical knowledge and skill. Teaching, like racing, seems to have become another directly delightful endeavor made possible by Matt’s professional skills which unlike racing also comes with a paycheck. (Our universities may do well to employ this strategy of hiring seasoned practical experts more often.) After four years the school asked Matt if he could expand the program to full automotive repair and begin teaching full time. Having experimented part time, Matt had discovered where his heart was and in his early fifties made a major career change leaving his power sports business to become an educator, but he retained one part of the old business. His Porsche restoration business continues to this day. As accrued expertise spawned more opportunity Matt was able to prune the professional bush back to the most enjoyable branches which today are teaching mechanics and racing, building and repairing air-cooled Porsches, and racing. The synergies between his different endeavors remain. In the center of his Porsche workshop right now is a pristine 1974 914 with freshly flared fenders, a project being undertaken with the assistance of his university students and which will eventually race under the university’s sponsorship (replacing the current vehicle of the university racing team, a dutiful Mazda Miata which has seen better days).

As I interview Matt there is a loud clanking coming from one of his former students turned apprentice beating on a crankshaft a few yards away. By apprentice I mean apprentice. These skills cannot be learned at any school in the country, nor is it something Matt could teach more than one person at a time. I know Jared too. He’s usually working in the shop when I come in. He has told me on multiple occasions how much he likes to come to work which when you think about it is a rather remarkable claim. The shop is something of an unexpected paradise inside compared to its ordinary exterior - a metal building that gives no hint of what kind of business is inside. On any given day there will be six or seven Porsches inside, a few on lifts. Today there is a Karmen Ghia and a Lotus interloping (at least the Karmen Ghia is air-cooled). There are three engines on stands mid-rebuild. Porsche parts and posters decorate the walls along with over 100 Porsche hot wheels, all different, gifted to Matt by his students. It’s hard to leave the shop without having contracted a bit of swagger in one’s step. The energy of real skill applied directly towards the creation of something breathlessly beautiful in appearance, sounds, and thrill bleeds into a person just by being there.

The problem they are urgently troubleshooting when I arrive is an electrical issue causing the fuel pump to fail (at least that’s their current theory) on the Lotus (British cars always have electrical problems) for which they have removed both seats and are tracing wires without the aid of a diagram which they were unable to find online. It has to be ready for a show in two days. By some kind of cosmic coincidence, the building Matt’s shop now fills was his professional home decades ago, although then he only occupied a small fraction of it. It is at the end of an obscure dead-end road and has no signage. Matt works by referral only, does not advertise, and made me swear not to give up the precise location of his shop, nor post images of it to social media. (That’s right - these pics are an American Hombre exclusive!)

How does Matt’s career rank on the danger scale? His early mentor Kevin Kuhle, the man who gave Matt his first real mechanic job, died at age 50 from injuries sustained in a racing accident years earlier. Matt himself is in excellent health though he’s had his own close encounters with death associated with snowmobiles not cars. He’s been in two avalanches. In the first and worse of the two, a three foot slab at the top of a cirque broke all the way down to the dirt. As his sled sank into the snow he was able to keep his body on top of the slab a little longer until he hooked a tree trunk with his arm and hung on for dear life. After the chaos blew past Matt found his horizontal body had turned vertical. He was standing straight up, boots on the dirt, still hugging the tree. He walked down the mountain to find his friends frantically probing the snow for his body and was met with a string of obscenities when they finally noticed him trudging down the hill. His snowmobile was buried four feet deep standing on end.

Another time the reed valve on Matt’s two-stroke snowmobile motor broke leaving him with one cylinder too few to power his climb out of the basin he was at the bottom of. The thing about being stuck in the mountains in the winter is that the depth of the snow doesn’t exactly allow a stranded snowmobiler or skier to leisurely amble back to the car. A 10 minute ride on a snowmobile might mean a day or more worth of postholing back in your boots. Matt didn’t have any snowshoes but he did have his tools. He opened up the engine, confirmed his suspicion that he had a bad reed valve, then manufactured a new one out of a credit card which lasted long enough to power him out of the valley plus fifteen miles back to home base.

Matt’s biggest professional fear has always been either ending up in a cubicle or somehow ending up as a minivan mechanic. He concedes a lot of cubicle employees make good money and many more money than he does and have more certainty in their job (although maybe less security than he supposes). “But you know what - they’re thinking about retirement. They worry about when they can retire and I worry that someday I might have to retire.“ I would also contend that the diversity of his working life could be evidence for stability - his skills have broad application - as compared to many cubicle dwellers with specializations mostly for the company employing them. As far as the minivan fear, its another indication to me that it isn’t just the motions we go through- what our work is -- that matters, but what the end result is. That seems obvious, but it seems most people think more about the motions they’ll go through than the result they’ll generate - perhaps because we’ve all given up on doing something that matters and only hope that whatever job we end up with isn’t miserable.

Matt tells me the most special thing about air-cooled engines is how they sound. I admit that I find myself rolling down the windows in underground parking and seeking out tunnels to accelerate through so I can better hear the resonant gurgle of my own car’s motor. Air-cooled engines, like cold-blooded animals, have less control over their own temperature and thus must be built to operate within a much wider internal temperature range than liquid-cooled engines. It is these greater tolerances Matt explains, that make the engine sound so beautiful. The noise betrays a richness that emanates from depth and solidity more at ease than most to its own changing structure. It’s easier for me, from my perch in corporate employment, than for Matt to see the metaphor which this is for his career. Matt exults in the multi-faceted aspects of his diverse work--variety which springs not from serially seeking sequential opportunity, but which flowers from a foundation of skill and passion. While most people try to read the future and bet their careers on the coming wave, Matt’s work is much more deeply rooted. It began with a mother insistent on matching her son with a hobby that magnified an innate ability which she saw more clearly than he did. While one may be tempted to conclude that Matt hit the professional lottery, it is telling the diversity of expression Matt’s skills and enthusiasm have found. From small garage work, to building and operating dealerships, to teaching mechanics and racing, to repairing and cruising hovercrafts with students in the university parking lot, Matt’s skills and interests have brought him days wildly more varied and unpredictable than the average office worker of course, but also more varied than the average mechanic. May all of us learn from Matt not to merely seek a resume that resonates with the latest trends, but which cultivates skill that will blossom in other areas of our lives.